In a recent groundbreaking study, anthropologists and archaeologists have unearthed evidence of a macabre practice from Europe’s Upper Paleolithic period. The findings suggest that humans who lived in this era, nearly 18,000 years ago, may have consumed the brains of their dead enemies. This discovery not only reveals a dark aspect of survival behaviors but also provides new insights into the cultural, spiritual, and dietary habits of ancient humans.

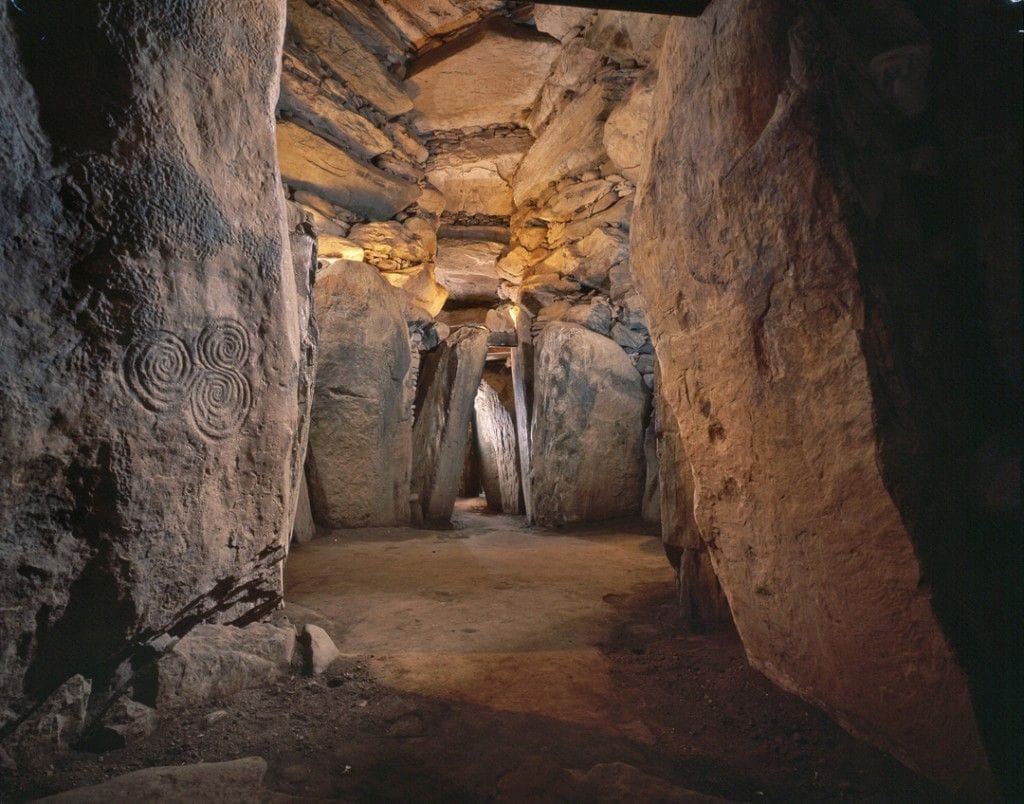

Scientists reached this conclusion following meticulous analysis of ancient human remains unearthed at archaeological dig sites in Europe. The skeletal remains showed distinctive signs of perimortem manipulation—alterations to the bone structure made shortly after death. Of particular interest were skulls that bore purposeful incisions and fractures, indicative of the deliberate removal of brain tissues.

The practice, though shocking to modern sensibilities, is believed to have served multiple potential functions. Researchers postulate that consuming the brains of deceased individuals could have been a way to honor and absorb the spirit or life force of the dead. Alternatively, it may have been an act of ritualistic dominance, aimed at assimilating the power of vanquished enemies.

There is also a purely utilitarian explanation, rooted in survival. The Upper Paleolithic era, while rich in cultural innovation, was also a challenging time for food security and environmental uncertainty. The human brain, being a protein-dense organ, may have been seen as a valuable source of nutrition amid scarce resources.

The research team supporting this hypothesis comprises interdisciplinary experts in physical anthropology, archaeology, and forensic biology. They utilized advanced imaging technologies, such as 3D reconstructions of ancient skulls, to identify distinct and repeated patterns of damage. In conjunction with minute bone analysis and carbon dating, the results strongly indicate intentional acts.

This new discovery fits into a body of anthropological evidence suggesting that human practices surrounding death have always been diverse and often symbolic. Funeral rituals in prehistoric cultures ranged widely—from burials adorned with intricate grave goods to instances of defleshing and excarnation. While macabre by contemporary standards, these practices carried deep meaning for the societies that engaged in them.

What makes this finding particularly impactful is its contribution to the understanding of Paleolithic human dynamics. Evidence of brain consumption could challenge existing concepts of prehistoric solidarity, cooperation, and conflict. Did such acts occur in the context of warfare, as a way to denigrate enemies? Or were they reserved for in-group rituals, perhaps honoring the deeply spiritual association that many ancient cultures had with the human body?

Despite these recent advancements, many questions remain. With limited data, it’s difficult to extrapolate the scale or purposes of the practices. Furthermore, the social context—whether spiritual or survivalist—is challenging to interpret with certainty, given the absence of written records dating to that era.

However, researchers emphasize that these discoveries should not be interpreted as indications of barbarism or primitive cruelty. Instead, they reflect the diversity of human responses to adversity and the profound complexity of Paleolithic cultures. These were communities grappling with survival, spiritual significance, and the establishment of social norms in environments far harsher than most humans confront today.

Scientists also highlight that humanity has long exhibited a wide range of behaviors in its relationship to the dead. Such cultural expressions are not confined to ancient history—ritualistic cannibalism, for example, persisted in various societies into modern times. Among prehistoric cultures, such behaviors were likely adaptive, symbolic, and informed by the ecological conditions of the time.

Looking ahead, researchers hope to broaden their investigations to include findings from other regions and time periods. The improved understanding of early human cultural practices will shed light on the evolution of spiritual beliefs, societal structures, and survival strategies.

As this study demonstrates, archaeology constantly redefines human history. Whether puzzling out the motivations behind gravesites, repurposed remains, or ritualistic behaviors, each discovery creates a richer narrative of humanity’s past. The practice of consuming brains 18,000 years ago may seem foreign to us, but it illuminates the ways humans adapt to their realities and endow their existence with meaning—even under the most extreme circumstances.